How Anchoring Bias Distorts Money Decisions

Anchoring is when the first piece of information sets the tone for everything else. This information is called the anchor. Once that anchor is set, all subsequent decisions are made in relation to it.

A good example of this was when I was at a former workplace during my youth service. My coworker, a fellow corper, was at the office, playing with an 8-year-old child. I asked her, “Who is the child?” She said, “She’s my sister.” For the next 30 seconds, I watched both the kid and my coworker and determined that they had a resemblance. I said, “She actually looks like you.” She laughed and said, “I was just joking, it’s the boss’s child.”

It took me years to realize that I had fallen victim to the anchoring bias. The anchor being, “she’s my sister.” But even though it was false information, a joke, my brain made the wrong conclusion because of the anchor. And after I was already informed that the child wasn’t her sister, I still insisted that they looked alike.

It’s possible that they shared facial features, but I’m sure that if you look at any two human beings long enough, you can find some similarities between them. But anchoring biased me into thinking that whatever similarities they had were because they were siblings, instead of just letting it go.

What makes the anchoring bias so dangerous is that even after you find out the anchor is wrong, the brain might still stubbornly hang on to the conclusions you made due to the bad information. We don’t like being wrong. Our mind likes to be internally consistent. If we concluded, we tend to believe it’s because we considered the right factors, even if the premise was bad. As you can probably guess, holding on to the first piece of information you encounter can be dangerous in many areas of life. In personal finance, especially, rational thinking matters— from negotiations to investments to everyday purchasing decisions.

Ingrained Ideas

What we believe about any particular topic is very subject to bias, such that if we don’t consciously rethink or question our beliefs, we may be basing any decisions we make on a lie or half-truth.

How much of an adult’s belief about themselves is based on the first info given to them by an authority figure when they were a child, like parents or teachers?

For example, an adult with low self-esteem who was told that they were stupid by their parents may grow up believing that is true. A child who was told that they are dull with academics may grow up believing that they are dull. It becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy if they don’t question it at some point.

This applies to so many other things. Most people don’t choose their religion; they inherited it because that was the first belief system they encountered. Growing up, your school fees were always paid.

Emergency money always came from home. As an adult, you unconsciously assume: “If anything happens, someone will help.” That early experience becomes an anchor even when the people involved are aging, financially stretched, and have new priorities.

Or you grow up hearing: “This house will be yours.” “That land is for you.” Without realizing it, you: save less, delay investing, and take more risks. Once you understand how easily the mind anchors to the first explanations about anything, it becomes impossible to believe that many decisions are purely rational.

Other Money Beliefs

- “I’m bad with money.”

- “I will never be rich.”

- “Rich people are evil.”

- “To be wealthy, you have to do bad things.”

- “Investing is risky; you will lose your money for sure.”

- “Money is meant to be spent and enjoyed. Savings is a waste of time; tomorrow is not guaranteed.”

Ask yourself, where did this belief come from? Was it from childhood? Was it from a person of authority: a parent, teacher, neighbourhood bros, an older sibling, or someone you admire? Have you questioned it? Asked if these beliefs are really true?

Self-Defense

The best way to question your beliefs is to look for evidence contrary to your belief and try to understand the opposite perspective, genuinely. For example, if you believe that saving money is a waste of time, you should look for alternative perspectives from people who believe that saving money changed their lives.

If you have always saved 20% of your salary for years when you were earning ₦200,000, and then your salary increases to ₦1.2 million, you may keep believing that you are supposed to keep saving 20%. Even though your disposable income has increased drastically. Start by exposing yourself to saving more than 20% on a small scale at first, and then, before raising your savings rate drastically.

If you think investments are risky, do some research on people who have invested successfully for decades. Research low-risk investments and then slowly expose yourself to buying them.

Key Takeaway: seek out the opposite perspective, test it in small ways, weigh the pros and cons, then decide.

Negotiations

This bias is very active in negotiations because with negotiations, someone has to give the first number— a price, an offer, an ask.

The First Salary

You earned ₦250k at your first job. Four years later, an offer of ₦400k at a new job may feel good even if your skills have doubled, inflation has exploded, and your actual market value is now ₦700,000. You’ve anchored any new salary in relation to the initial first salary of ₦250k. Any extra money feels like a bonus to you, and may discourage you from negotiating because you feel like at least it’s better than your first salary.

The First Offer

There’s a reason job seekers are told not to say their expected salary first because the first number in any negotiation usually dictates the baseline. People don’t like to stray too far from the anchor. If an HR manager says, “What are your salary expectations?” and you nervously say ₦300k, you have set the anchor. Even if the company’s budget was ₦500k, you would have reset the baseline, and negotiations would now revolve around ₦300k.

Very rarely will a company try to pay you more than they can get away with. That’s HR doing the Balogun market dance, but with your career. So instead of giving the first number, you could say, “I’m more interested in finding the right fit for my skills and learning about the company. What’s the budgeted salary range for this position?”

Some companies may insist that you give them a number even if you try to maneuver your way out of it. So you could just say, “After researching similar roles with my skills and years of experience, the market value for my role is within a range of ₦700k – ₦1.2 million.” Make sure that the first number in the range that you call actually favours you, in this case, ₦700k. Make

it as high as you can get away with without irritating your potential employer.

The rule is that if you are forced to call the first number, make it as high as you can. This is why lawsuits always mention a ridiculously large amount as a suggested settlement number when they first sue. This is also why in the market, because sellers are forced to call the first number, they go as high as they can without chasing the customer.

You: “How much?”

Seller: “My sister, for you, ₦30,000. “

Narrator: “Actual worth is ₦10,000. You beat him down to ₦15,000, and now you feel like a negotiation genius. In reality, he still made ₦5,000 extra because he raised the baseline.”

Self Defense

Before you go into a negotiation, know what value you are willing to accept. Arm yourself with market research for product prices or role salaries. Don’t accept the first number you are offered, either. Resist the anchor. When possible, don’t necessarily commit to the first offer/vendor you encounter. Shop around for better offers and compare.

Ultimately, determine your walk-away point beforehand. To learn more, read about BATNA. Delay works too. You are allowed to think about an offer or come back after weighing your options. Delay helps reduce the effectiveness of the bias, because time gives your rational mind space to override the bias.

Sales

Discount

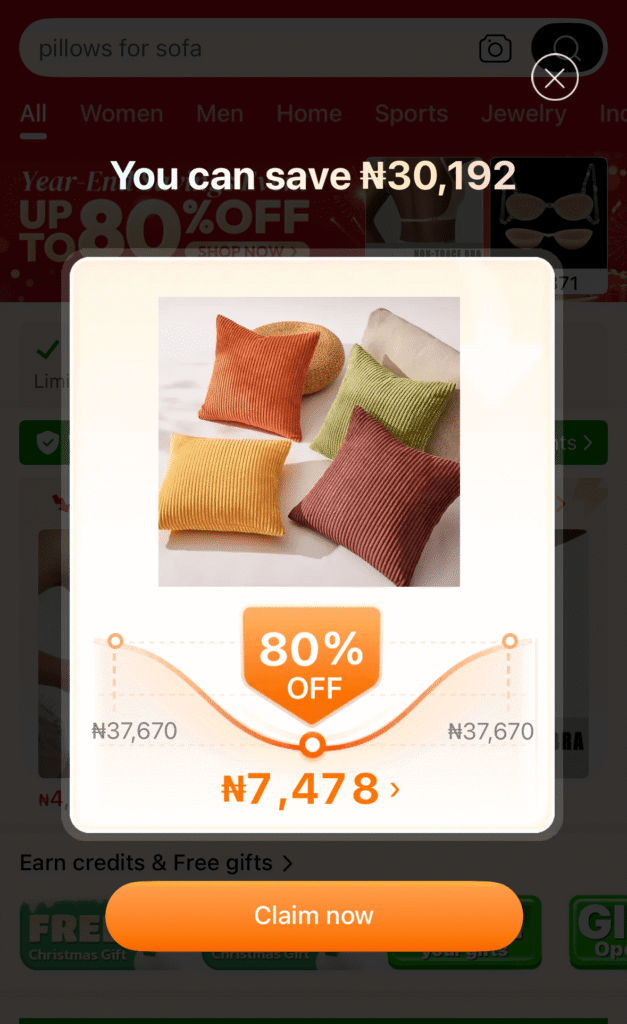

When we see items that are marked as a discount, e.g., was ₦10,000, now ₦3,000, our brain anchors on the first price, ₦10K, as the true value of the item, and thinks ₦3K must be a steal. So we rush the item because we think it’s a great deal. Reality: ₦3K might be the actual value.

E-commerce sites like Jumia and Temu do this all the time, especially Temu, with their “₦68,000, now ₦25,000 after discount was applied.” Even when you consciously know that it’s a trick, it still works, because it bypasses the rational part of your brain.

JCPenney, an American chain store that sells clothes, used discounts to a large degree in its product presentation and made a killing. But in 2012, they got a new CEO who decided to get rid of all the deals and give all items an outright price: no more sales, bargains, or discounts.

He tried to replace the “fake price” discounts and just slapped on the original low price on the products, but it backfired. Sales tanked dramatically. Before the CEO was hired, people had claimed to hate these “fake, inflated” discount prices, but in reality, it’s not that the realistic prices actually made them sad; it’s just that people loved feeling like they got a bargain.

Product placement

Businesses often show expensive items first as an effective use of price anchoring. A restaurant menu that places the most expensive items first creates a perception of the food being expensive. But if you flip the pages and see less expensive options, you might feel a sense of relief.

Menu consultants have admitted to presenting ridiculously expensive menu items first on purpose, not because they actually wanted to sell the more expensive option, but to make you feel like you got a bargain when you eventually see the less expensive option.

₦20,000 for a plate of jollof rice is expensive on its own, but if it comes after a ₦80,000 plate of seafood rice, the ₦20,000 rice suddenly seems like a bargain. This is why you must learn to evaluate items based on their actual value, but not in relation to an anchor that was strategically placed first to manipulate you.

Self-Defense

Anchoring in sales relies on you basing the value of the product on the anchor price, but you must find a way to resist and evaluate the product on its own value and its affordability for you. Before you expose yourself to the prices, ask yourself what price you are willing to pay for a product or experience.

When you see one of those “Was ₦10,000 now ₦3000” displays, ask: “Would I buy this for ₦3000, if I never saw ₦10,000?” Don’t think about: “limited offer”, “deal”, or “percentage saved”. Those are noise. The only thing that should matter is how much you’d be willing to pay if you didn’t see the anchor price.

Summary

The anchoring bias is embedded in our everyday life and affects how we make our decisions. Based on our first introduction to a topic, opinion, argument, number, product placement, belief, or anything. These shape our thinking in hidden and sometimes visible ways.

You cannot stop anchors from being thrown at you. But you can decide which ones stick. Anchoring works best on people who don’t have budgets, research data, price ranges, or spending rules. Don’t let that be you.

You’ve crossed the first hurdle by being aware that this bias exists at all; the rest of the battle becomes dismantling bad judgments from false anchors in both your personal finances and the other areas of your life.

Can you try to spot more examples of anchoring in your daily life?